One thing that I’ve absolutely grown to adore in India is the friendly display of affection between men. In complete contrast to our own societal views, men have no qualms about nonchalantly taking the hand of their friend as they stroll the chaotic streets. It’s such a gentle, warm, humanistic sight amongst the urban bedlam. It’s almost protective, too, as if they are trying to shield their comrade from racing rickshaws and the periodic cow.

Back in Bengaluru, I found myself shaking the hand of a teacher. As they often tend to do here, it naturally transformed into interlocked hands as he questioned the certification process in the States. There we were. Two men. Two teachers. Surrounded by students. Holding hands. Ironically, it was I who became uncomfortable and I who awkwardly broke away. It was a stark reminder how thick our cultural lenses with which we view the world are.

As Mangala had mentioned to me, being gay in India isn’t even within the scope of possibilities. Many would debate me on this, I’m sure, but it’s almost like homophobia doesn’t exist because having a phobia assumes that you have recognized the existence of something and consequently feel threatened. In other words, arachnophobia wouldn’t exist without spiders, so since homosexuality “doesn’t exist,” neither does homophobia. Showing affection towards your same-sex counterpart, therefore, is just that. Friends being friendly. Isn’t it simultaneously refreshing and scary? Refreshing in that men aren’t afraid to show warmth, but scary that millions are living unfulfilled lives. As one American expat living in Mumbai told me, “The best part about moving here is that I can be whoever I want to be. Except gay.” Sex between men was illegal here until last year. “A landmark ruling,” to which I’ve heard it referred, overturned that remnant of conservative colonialism, but a public decree does not a culture change.

I knew that somewhere there had to be some secretive backdoor enclave of gay life, whatever that means. (Side note: I hate phrases like “gay life,” “gay scene,” and “gay culture” because they imply such homogeneity – Hahaha. Homogeneity of homos. That makes me giggle. – but that’s another issue, so I’ll use these flawed phrases for ease’s sake.) Mumbai, I figured, would be the best place to search since it seemed to be the most socially liberal (owing to the fact that bars are a common sight – not the case elsewhere), as well as the fact that it’s reputed to be the center of nightlife. Clubs abound. Apparently. So, who do you ask?

Duh. Google.

Here’s an experiment. Think of a major city around the world. New York City. Mexico City. Tokyo. London. Shanghai. Now type that place into the search bar followed by the word “gay.” How many sites pop up? Now try it with Bombay. Compare. Here are my results with the aforementioned cities:

NYC: 15,000,000

Mexico City: 8,060,000

Tokyo: 3,320,000

London: 26,900,000

Shanghai: 2,200,000

Bombay: 787,000

Telling, huh? With the exception of one bookstore tucked in the suburbs, there isn’t a single establishment whose business is primarily aimed at the gay population. From a purely capitalist perspective, this blows my mind. Let’s think in numbers, shall we? Of course there is no way to tell how many LGBT people there are in the world, but the oft used number is ten percent. Let’s just say that is a shockingly high number and go instead with five. With a population of 20 million+ in Greater Mumbai, we’re talking a million people. Let’s cut out a third as being minors. 666,000. Now, let’s assume that half don’t have the financial resources to spend at gay bars, bookstores, cafes, etc. 333,000 people. That’s huge. Of course, this is a totally bogus number because it completely ignores the larger cultural constructs that I already mentioned. It’s still interesting to let that number mentally marinate. If there were to be a gay bar/club, how many people would turn up?

A couple hundred it turns out. An organization named Gay Bombay was started to provide safe and open dialogue, as well as organize events. As luck would have it, there was a planned soiree the Saturday I was there. The gay fairy (haha) doubly blessed me as the planned locale was within walking distance of my hotel. I even went out and bought some jeans. That’s right, Mumbai. I was trying to make myself look good.

Before going, I browsed a few websites dedicated to Mumbai nightlife which made it sound like I was going to walk into some multilevel Bollywood version of Studio 54. There would be martinis. There would be famed DJs. There would be a reporter from Time Out.

There wasn’t.

It was a tiny hole of a place, two rooms, suggestive of a parent’s basement perhaps. Everything – the walls, the floor, the ceiling, the seating – was painted black. A few colored light bulbs flashed sporadically and a single green laser shot out from the diminutive DJ booth precariously perched above the dance floor.

I felt oddly comfortable, though. Clearly I’d never been there but I had this sensation of déjà vu. As I parked myself against some tacky mirrored wall, I tried to pick apart the feeling. Why was I standing there giddily smiling?

Madison, Wisconsin. Club Five. 2000. I was twenty years old. Yep – it felt exactly like that. See, Darren or Eric and I would drive an hour and half from Milwaukee to get to this dump of a gay club on the outskirts of Madison. They had underage night on some obscure night – Tuesday, maybe? We’d try to pass as being over 21 to get on the drinking side. If that didn’t work, we had some weird system of passing the magical bracelet that said you were of age. If that failed, too, we’d just dance the night away on the underage side. I don’t even know where we slept when we went. Maybe on the floor of some acquaintance’s apartment? Did we drive back to Milwaukee afterwards? Who the hell knows. What I do know, though, is that there was this vibrancy in the air there. Young men and women had found this beacon of a place where they could dance stupidly, wear ridiculous clothes that took hours to select, flirt shamelessly, maybe get a phone number, and just generally feel comfortable. It was liberating. For many, it was the first time they found people who felt like they did. As shallow and hedonistic as the “bar scene” may be, it was a formative place for many.

As I watched souls of all ages – 18? 60? Did it really matter? – enter this happy shack of a place in Mumbai, it was the same sentiment. There was hugging. There were animated stories. There was that gregarious twink unabashedly flailing about to some remix. Everyone here had found that same safe space that I had found in Club Five. Just like I had come of age in Madison, it seemed like all of Mumbai was coming of age here. It was a step in the right direction – a pretty big one if you think about it, one that stepped away from years of total denial of the LGBT population.

I ended up having an amazing evening after I let myself cave into my much younger self again. I drank. I danced. I chatted. I stayed until 2:00 am – which, for those of you know me, is a big deal. Normally this 29-going-on-83 year old is happily tucked in bed at that point. Someone even asked me if I wanted company for the night. Ooh la la. The 20 year old me, giddy on booze and possibility, might have said yes, but the older me, giddy on the thought of sleep, politely declined. I can only hold onto my early adult years for so long, right?

I have such amazing respect for each individual who showed up that night. Bless you. May you somehow find a freedom and a comfort to just be you. I wonder, though, as the number of courageous souls living openly increases how manifestations of amicable affection in India might change. I hope they won’t. Perhaps India will succeed where the Western world has failed. Maybe India will continue to be uniquely India and two men – whether they be friends or lovers – will simply be able to meander hand in hand.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Monday, July 26, 2010

An open letter to Jayne Bannon

Dear Jayne,

Let me start by saying this: You don’t know me. We’ll probably never meet, which isn’t something to lament since we’ve had a few similar experiences, the most forefront in our minds, I’m sure, are our respective trips to Mumbai. It’s oddly comforting knowing that a complete stranger has stood in the same place as you, don’t you think? I wonder if you let your eyes pause on the same gilded carriage regally rolling in front of the Gateway to India. I wonder if you watched the same elderly woman perform her morning prayer ritual alongside the spiritual Banganga Tank. We can be sure, however, that there was one thing in particular

Let me start by saying this: You don’t know me. We’ll probably never meet, which isn’t something to lament since we’ve had a few similar experiences, the most forefront in our minds, I’m sure, are our respective trips to Mumbai. It’s oddly comforting knowing that a complete stranger has stood in the same place as you, don’t you think? I wonder if you let your eyes pause on the same gilded carriage regally rolling in front of the Gateway to India. I wonder if you watched the same elderly woman perform her morning prayer ritual alongside the spiritual Banganga Tank. We can be sure, however, that there was one thing in particular

we both did: visit the National Gallery of Modern Art. I know this because we both signed the guest book. Maybe, like me, you were initially drawn to the building’s exterior and its location amongst a carefully planned esplanade of impressive structures boasting classical and gothic architecture. You know what I’ve always loved about gothic arches, Jayne? How they come to a point at the top as to say, “Screw you, perfect parabolas! What has classical architectures and its Doric columns done for me lately? We will drip with adornments of our own!” I digress.

Maybe, like me, you were surprised by the Guggenheim-esque interior. Curved galleries bathed in white invited you upwards until you reached the zenith, a completely circular space that presented us with 360 degrees of modern Indian visual manifestations. Did you find it peculiar not to recognize the name of a single artist? How horribly limiting and exclusionary our own museums and galleries must be!

Before the artsy gandering could begin, though, we had to pay the entrance fee, remember? Like every other national gallery or monument I’ve visited, foreign tourists have to pay a different fee than that of Indian nationals. In this case, we had to pay Rs. 150 ($3.30) whereas Indians had to pay Rs. 10. This apparently got you into a tizzy as this is what you wrote in the comments section of the guest book:

Jayne, my Jayne. Sweetheart. Where to begin? First, clarifications. No matter how many strongly worded compositions you may post, the Indian government won’t do a damn thing. They have instituted this policy nationwide. And fascism? Really? You’re being repressed at the tyrannical hands of… who? The man checking your bag? Asking you to pay three dollars is hardly a fascist act. And this statement about coming to your country and receiving loans? I mean, this is just so teeming with your own biases. It undoubtedly makes you sound like an overly-privileged cow of a woman who passively – and perhaps actively – loathes brown people but will visit their country of origin so that you can come back and lunch with your compatriots, emit pseudo compassion as you unctuously bemoan their economic condition, and then display the new silk rug you had shipped back. It makes you seem like the wealthy baron in Deepak Shinde’s painting “Master siesta” who expects to be waited on hand and foot while vacationing when really you should never travel beyond your backyard or the vacuous depths of the Louis Vuitton counter at Harrod’s. Notice, Jayne, that I said “you sound like” and “you seem like.” I didn’t say “you are.” I’m sure you’re a really nice person. Really.

Now, let’s move on to the heart of your grievance, that fire ant that seems to have bitten you where only your husband has touched. (Look at me making assumptions, Jayne. Maybe you’re not married? No worries. I’m not either.) You’re riled up about the tiered payment structure. You called it “disgusting.” You think “change is in order.” Let’s tease this out, shall we? First of all, we must assume that nearly 100% of foreign visitors (yes – you and me) are of a certain financial status. Being able to purchase an $800, $1200, $2000 airplane ticket – for vacation, no less – puts us in a particular bracket. On the flip side, the average yearly income in Mumbai is about $2300 (three times the national average). Clearly, paying Rs. 150 or even Rs. 10 for entrance to an art gallery is unthinkable for millions. Yet, no organization can subsist solely on ten rupee entrance fees. So – in a move towards equitable fees for all – should the gallery charge, say, Rs. 80 of everyone? If so, many more would be unable to enter. Are you okay with that? Would you dare to claim that art appreciation is an elitist activity and would therefore advocate for such a fee structure?

I suppose the ideal system would be a sliding scale based on income, but how would that work without some sort of identity card that was tied to your tax returns? That sounds rather Orwellian, doesn’t it? Another possibility would be to have a “suggested admission” like the Met and the Natural History Museum do in New York. The irony of that system, though, is that it’s mostly the locals who notice the “suggested” part. Those from Nebraska and the Netherlands merely look at the board and see the dollar sign and the fifteen. So the tourists pay more. And so it goes.

Despite 150 rupee entrance fees, I hope that you had the opportunity to enjoy the wonders of this metropolis, some accounts putting it as the second largest city in the world with roughly 14 million people in the city proper, many more if you consider Greater Mumbai. Perhaps, if you weren’t holed up in your hotel, you were able to experience all of the city’s idiosyncrasies, the continual flutter of activities that create this urban song of sorts. Set against the beat of horns and collapsing umbrellas, the stalls and markets sing deals of every good and service imaginable. An hour on Colaba Causeway offered me jewelry, drugs, faux antiques, authentic antiques, a haircut (odd, considering I don’t have much right now), a shave (that’s the exception… as much on my face as on my head), pashmina after pashmina, and an ear cleaning (complete with the hawker sticking his finger in my ear). Did you stop and wonder about the daily routine of the man who slept beneath the overhang of a kiosk, his head resting on his own detached prosthetic leg? Did you walk along Chowpatty or Juhu beach awkwardly trying to prop your open umbrella between your neck and shoulder so you could simultaneously eat the notorious bhel puri? Did you get on the train just to see what it’s like to be part of the most overcrowded public transportation system in the world?

Did you stare at the bullet holes in Leopold’s, remnants of the 2008 terrorist attacks and a badge of grit and perseverance that refuses to be patched? Did you duck into restaurant after restaurant seeking a culinary repose from the climatic rage outside? My favorite moment of the weekend was undoubtedly had in a Rajasthani thali restaurant. First of all, thali? Amazing. Five, eight, ten, maybe twelve different delicacies magically appear, most of which are absolutely nameless to me. There’s that spicy red sauce/soup (do I dip my chapatti in it or drink it?), that fried sweet thing dripping with some sugary syrup, that lentil concoction, the raita which crunches with cucumber, and those dishes that defy my futile attempts at description. As I planned my gastronomic attack, one of the waiters struck up a conversation with me, or rather – owing to my nonexistent Hindi and his limited English - struck up a combination of short phrases, gestures, and smiles. The one waiter grew to a pair, then a trio, a quartet, and finally a small ensemble of six, and a concerto of laughter commenced. It was lovely. Oh – since you’d be happy to know this – everybody in the place is charged the same amount.

Did you stare at the bullet holes in Leopold’s, remnants of the 2008 terrorist attacks and a badge of grit and perseverance that refuses to be patched? Did you duck into restaurant after restaurant seeking a culinary repose from the climatic rage outside? My favorite moment of the weekend was undoubtedly had in a Rajasthani thali restaurant. First of all, thali? Amazing. Five, eight, ten, maybe twelve different delicacies magically appear, most of which are absolutely nameless to me. There’s that spicy red sauce/soup (do I dip my chapatti in it or drink it?), that fried sweet thing dripping with some sugary syrup, that lentil concoction, the raita which crunches with cucumber, and those dishes that defy my futile attempts at description. As I planned my gastronomic attack, one of the waiters struck up a conversation with me, or rather – owing to my nonexistent Hindi and his limited English - struck up a combination of short phrases, gestures, and smiles. The one waiter grew to a pair, then a trio, a quartet, and finally a small ensemble of six, and a concerto of laughter commenced. It was lovely. Oh – since you’d be happy to know this – everybody in the place is charged the same amount. These are the moments, Jayne, upon which we should fixate. These educate us, force us to be more compassionate, and grace us with the tiniest glimpse into the existence of our neighbors. They’re like that golden rope lassoed around the red velvet stage curtain. We, the audience, are blessed as it tightens, briefly removing the barrier between two distinct experiences. In Friday’s NY Times, David Brooks had an op-ed piece about moral naturalists. This group believes that the moral fabric woven into modern and ancient

society is not necessarily the result of lectures from our mothers or spiritual leaders, but rather the result of relationships and interactions. Brooks wrote, “People who behave morally don’t generally do it because they have greater knowledge; they do it because they have a greater sensitivity to other people’s points of view.” I couldn’t agree more.

So, Jayne, maybe it’s time to truly benefit from the travels in which we are so fortunate to partake. So we have to pay a bit more to enter a museum. So we probably get driven an extra block by the rick-wallah to get a bit higher fare. So we get a stomach bug. Big fucking deal. It is the experience that draws you, me, and every other traveler.

With that, my dearest Jayne, I must run. An adventurous and head-spinning taxi ride to the airport awaits, as do my upcoming adventures in Udaipur. My greatest hope is that your next trip will find you with your eyes open, your thoughts available, and your heart unbounded.

As the Mumbai railway tickets state, “Happy Journey.”

Be well,

Joe

Saturday, July 24, 2010

Origins of nutmeg

I was about to say I was reminded of this fact over the last couple days, that everything has an origin and by consuming it we are interacting with other people around the world. But – was I really reminded? Or was today the first time I really thought about it?

Let’s restate:

I was shown this fact over the last couple days, especially as I visited a spice plantation tucked in the tropical hills around Panaji.

As I crossed the handmade pedestrian bridge (Where did these logs come from? Who put them here? Was it the same person who cut them down?), I was greeted by grazing water buffalo, unremitting rain, towering palms, and a smiling tour guide. He shook my hand, welcomed me to the Tropical Spice Farm, and handed me a “welcome drink” – a tea made of cardamom, lemon grass, and ginger. Apparently it was good for curing colds, ending indigestion, and easing anxiety. Not really afflicted by any of these woes (Anxiety? On vacation? Nope.), I was content with the fourth benefit: It tasted really good.

A small group formed – a Malaysian engineer now living in Paris, a vacationing family from Delhi, a scraggly black dog, me – and shortly thereafter we were trailing the guide and discovering the origin of the spices that haphazardly and chaotically inhabit the cupboard next to our stove. (Side note: I’m so envious of my mom’s spice cabinet. It’s organized alphabetically and utilizes tiered lazy Susans. I dream of such luxuries…)

I cannot count the number of times I let out an audible “Huh.” Not “Huh?” the question, but the “huh” with the inflection in the middle that means “Wow. I never knew that.” Did you know that…

• Bay leaves and cinnamon come from the same tree? You just scrape the bark off and – voilà – you have cinnamon. Knowing that, aren’t the cinnamon sticks we find at the store weird? They look nothing like bark. What the hell does McCormick’s do to make it look like that? Just give me the bark.

• Nutmeg requires both a male and female tree to be produced? The branches of each must touch one another in order to pollinate. To maximize space, a single male tree is planted in the middle of six female trees. What a botanical slut.

• Vanilla, the second most expensive spice in the world, must be pollinated by hand? Yep – every single flower. Also, dried vanilla beans should be rubbery. You should be able to wrap it around your finger. If you can’t – don’t use it. It’s not fresh. And the most expensive spice in the world? Saffron. It costs more than gold.

• Allspice isn’t a combination of various spices, but rather a single plant (which looks strikingly similar to some boring houseplant) whose green leaves simultaneously have the scent of cinnamon, nutmeg, and cloves?

Despite the fact that ¿De dónde eres? is one of the first phrases taught in my classes, I had never asked that same question of my spice cabinet.

I again questioned origin while strolling the beach of Candolim. Desolate save a young couple wanting a place to canoodle (Sorry, by the way, for destroying your privacy), I was kept company by crashing waves, sheets of rain, amazingly green surroundings… and a gigantic beached industrial tanker.

Where the hell did that come from? It was, in a word, weird… and a little creepy. I mean, it was this absolutely gargantuan ship, rusted and ominous, looming over the entirety of the coast like some symbolic doomsday. The couple, arms around one another, seemed oblivious whereas I felt like it would leap out of the sea, bare fangs, and eat me in some gruesome Jaws-like chomp.

My line of questioning origin continued in Old Goa where the classical architecture – and prevalence of churches, chapels, and monasteries – led me to feel like I was in Latin America, another region familiar with the effects of colonialism. Entering the Sé Cathedral, the largest church in Asia, felt bizarre (Okay, it always feels weird for me to walk in a church, but that’s another story). I’m not trying to discount the religion of 24 million people in India, but the whole existence of Christianity here felt oddly imported. I suppose you could say that Christianity was imported to the States, as well, but there are many who would say the US is now a Christian nation. Clearly, with millions who practice Islam, Judaism, Hindu, etc. - not to mention a growing number of agnostics and atheists – this is an exclusionary, if not fictitious, statement.

Is religion just some cultural construct or manifestation? If so, are the religions that spread due to colonization or proselytization (i.e. Catholicism) just remnants of imperial tyranny? Moreover, if we can accept that Christianity was a European export (it would be hard to debate that) at what point does the imported product – in this case, religion – become a nationally grown entity? Have its roots in colonization disappeared – or rather been forgotten – consequently making it a “New World” product with a born on date of 1700? 1800? My point isn’t to chide religion (or bottled spices or large ships), but rather to question whether we question. Where did it come from?

I can’t let it stay there too long, though, since I have a flight to Mumbai in a couple hours. I sip my chai, nosh on the food that’s still on the plate, and stare down at the street from the balcony. Girls in plaid uniforms sheepishly glance up at me and giggle. A bike horn sounds. I smile. The sun has come out. Now, I ask myself, after a week of incessant rain, where did that come from???

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

Reflections on a monsoon

It was 7:45 on Sunday morning. Having arrived to Varkala, Kerala the day before after a fifteen hour train ride, Mangala, Natasha, and Ajay were still sleeping. I, awoken by the duet of a monsoon and the crashing waves of the Arabian Sea, slipped out to the verandah to read. I didn’t get too far, though, in The Catcher in the Rye. I mean, how could I? What spread out before me was idyllic. Our hotel – an 85-year-old cliff-top home converted into beautifully simple rooms – was enveloped in the rich green that only comes with the monsoon season. Palm trees wearing coconut necklaces stretched out at an angle to be closer to the sea. Streams of water raced down the crevices of the tiled roof, falling to the ground with restorative rhythm. It was calming. I felt like I had just walked out of a great therapy session, but all I had done was woken up and walked outside. Life was good.

A funny thing happens when it storms over the ocean: the water and the sky become the exact same color. I stared at the horizon – or, rather, where I thought the horizon should be – and only saw a swath of pale grey. Two elements had become one. There was absolutely no separation.

Our aforementioned train journey from Bengaluru to Kerala was very similar, in a sense. Walking into our berth, we were suddenly at home with a handful of other people: a portly, mustachioed “uncle” of a man, his wife – “Aunty”, and this tiny young bespectacled woman who giggled incessantly at our admittedly ridiculous conversations. Like the monsoon before me in Varkala, there was no separation between us. Mangala offered food and games. Uncle offered advice. Tiny woman offered us a chance to laugh at ourselves. Throw in passing men touting coffee coffee coffee chai chai chai biriyani biriyani biriyani and it was a microscopic mobile community. We felt some sort of kinship with the tiny woman, which struck me. How many times have I been on a plane and been seriously irritated by someone wanting to chat with me? How many times have I put in headphones – music not necessarily playing – as a precautionary measure to avoid small talk? Why was I open to this exchange of humanity here but not elsewhere? Why had there always been a divide in the past but here it disappeared?

I suppose some of the answer could be found in the much more familial and communal culture here. Also, as Mangala said in passing, with over a billion people (one sixth of the world’s population) in India, personal space is something that many simply don’t experience. Those no-fly zones that we have constructed around our bodies don’t exist here so this sense of community has been ingrained into the larger national and cultural psyche.

I suppose some of the answer could be found in the much more familial and communal culture here. Also, as Mangala said in passing, with over a billion people (one sixth of the world’s population) in India, personal space is something that many simply don’t experience. Those no-fly zones that we have constructed around our bodies don’t exist here so this sense of community has been ingrained into the larger national and cultural psyche.

I cannot begin to count the number of chats I’ve had as I’ve meandered around five different Indian states. They usually follow a prescribed questioning order, with numbers two and three being interchangeable:

From there, the conversation circuitously strolls, sometimes touching on family, religion, my impressions of India, and – in one very bizarre case in Cubbon Park in Bengaluru – a proposition for sex.

I declined.

Coital proposals aside, it has been nice to feel like these arbitrary walls I have built up around me have started to fall. I’ve given myself the liberty to let my mind wander and – dare I say it – relax. I feel like my vision had become myopic over the past year, solely focusing my thoughts on work or failing relationships. It was a false bifurcation, either thinking about the water or the sky. I didn’t let the entire human experience melt together into a single shade where I could freely move from one area of thought and inquiry to another. As a result, I found myself on first dates with nothing to talk about because I had only thought about a handful of topics. In Varkala, though, mornings of chai and books morphed into afternoons of appams and cliff-top explorations which turned into evenings of Kingfishers and laughs. My mind jumped from grammatical differences between Hindi, Kannada, and Punjabi to the joy of the lungi. We laughed about Britney Spears concerts and the excessive amount of oil used in our ayurvedic massages (Seriously, a strong breeze would have sent our loin-clothed bodies flying off the massage table and down the hallway like a slip-n-slide). All the synapses in my brain – not just a measly pair – had been reconnected and were flourishing on the new input.

Coital proposals aside, it has been nice to feel like these arbitrary walls I have built up around me have started to fall. I’ve given myself the liberty to let my mind wander and – dare I say it – relax. I feel like my vision had become myopic over the past year, solely focusing my thoughts on work or failing relationships. It was a false bifurcation, either thinking about the water or the sky. I didn’t let the entire human experience melt together into a single shade where I could freely move from one area of thought and inquiry to another. As a result, I found myself on first dates with nothing to talk about because I had only thought about a handful of topics. In Varkala, though, mornings of chai and books morphed into afternoons of appams and cliff-top explorations which turned into evenings of Kingfishers and laughs. My mind jumped from grammatical differences between Hindi, Kannada, and Punjabi to the joy of the lungi. We laughed about Britney Spears concerts and the excessive amount of oil used in our ayurvedic massages (Seriously, a strong breeze would have sent our loin-clothed bodies flying off the massage table and down the hallway like a slip-n-slide). All the synapses in my brain – not just a measly pair – had been reconnected and were flourishing on the new input.

A funny thing happens when it storms over the ocean: the water and the sky become the exact same color. I stared at the horizon – or, rather, where I thought the horizon should be – and only saw a swath of pale grey. Two elements had become one. There was absolutely no separation.

Our aforementioned train journey from Bengaluru to Kerala was very similar, in a sense. Walking into our berth, we were suddenly at home with a handful of other people: a portly, mustachioed “uncle” of a man, his wife – “Aunty”, and this tiny young bespectacled woman who giggled incessantly at our admittedly ridiculous conversations. Like the monsoon before me in Varkala, there was no separation between us. Mangala offered food and games. Uncle offered advice. Tiny woman offered us a chance to laugh at ourselves. Throw in passing men touting coffee coffee coffee chai chai chai biriyani biriyani biriyani and it was a microscopic mobile community. We felt some sort of kinship with the tiny woman, which struck me. How many times have I been on a plane and been seriously irritated by someone wanting to chat with me? How many times have I put in headphones – music not necessarily playing – as a precautionary measure to avoid small talk? Why was I open to this exchange of humanity here but not elsewhere? Why had there always been a divide in the past but here it disappeared?

I suppose some of the answer could be found in the much more familial and communal culture here. Also, as Mangala said in passing, with over a billion people (one sixth of the world’s population) in India, personal space is something that many simply don’t experience. Those no-fly zones that we have constructed around our bodies don’t exist here so this sense of community has been ingrained into the larger national and cultural psyche.

I suppose some of the answer could be found in the much more familial and communal culture here. Also, as Mangala said in passing, with over a billion people (one sixth of the world’s population) in India, personal space is something that many simply don’t experience. Those no-fly zones that we have constructed around our bodies don’t exist here so this sense of community has been ingrained into the larger national and cultural psyche.This idea of a shared experience is completely universal, I think, in childhood, but somehow we lose it as we grow older. Walking into a migrant labor school in Bengaluru, Mangala and I were happily bombarded with hugs and handshakes, cartwheels and frog jumps, and general merriment. Despite the geographical, cultural, linguistic, and economic differences between these kiddos and the first graders I worked with in Boston last year, they were exactly the same. There was still the same level of curiosity and willingness to engage in conversation with a total stranger. While every adult seems to lose the eagerness to mimic a frog (is this a good thing?), we seem to fold up into a solitary cocoon whereas the interest in others – neighbors, strangers, guy sitting next to you on the G-train – continues to flourish here.

I cannot begin to count the number of chats I’ve had as I’ve meandered around five different Indian states. They usually follow a prescribed questioning order, with numbers two and three being interchangeable:

2. What do you do?

3. Are you married?

4. And your good name?

From there, the conversation circuitously strolls, sometimes touching on family, religion, my impressions of India, and – in one very bizarre case in Cubbon Park in Bengaluru – a proposition for sex.

I declined.

Coital proposals aside, it has been nice to feel like these arbitrary walls I have built up around me have started to fall. I’ve given myself the liberty to let my mind wander and – dare I say it – relax. I feel like my vision had become myopic over the past year, solely focusing my thoughts on work or failing relationships. It was a false bifurcation, either thinking about the water or the sky. I didn’t let the entire human experience melt together into a single shade where I could freely move from one area of thought and inquiry to another. As a result, I found myself on first dates with nothing to talk about because I had only thought about a handful of topics. In Varkala, though, mornings of chai and books morphed into afternoons of appams and cliff-top explorations which turned into evenings of Kingfishers and laughs. My mind jumped from grammatical differences between Hindi, Kannada, and Punjabi to the joy of the lungi. We laughed about Britney Spears concerts and the excessive amount of oil used in our ayurvedic massages (Seriously, a strong breeze would have sent our loin-clothed bodies flying off the massage table and down the hallway like a slip-n-slide). All the synapses in my brain – not just a measly pair – had been reconnected and were flourishing on the new input.

Coital proposals aside, it has been nice to feel like these arbitrary walls I have built up around me have started to fall. I’ve given myself the liberty to let my mind wander and – dare I say it – relax. I feel like my vision had become myopic over the past year, solely focusing my thoughts on work or failing relationships. It was a false bifurcation, either thinking about the water or the sky. I didn’t let the entire human experience melt together into a single shade where I could freely move from one area of thought and inquiry to another. As a result, I found myself on first dates with nothing to talk about because I had only thought about a handful of topics. In Varkala, though, mornings of chai and books morphed into afternoons of appams and cliff-top explorations which turned into evenings of Kingfishers and laughs. My mind jumped from grammatical differences between Hindi, Kannada, and Punjabi to the joy of the lungi. We laughed about Britney Spears concerts and the excessive amount of oil used in our ayurvedic massages (Seriously, a strong breeze would have sent our loin-clothed bodies flying off the massage table and down the hallway like a slip-n-slide). All the synapses in my brain – not just a measly pair – had been reconnected and were flourishing on the new input.I finally was able to focus on The Catcher in the Rye, one of those “classics” that I’d somehow never read before. I don’t know if I’d call it the most stunning piece of literature, but I did appreciate the protagonist’s rather stream-of-consciousness thought process. Jumping from films to depression to girls to Catholics, Holden’s notions were without borders, without separation. There were no lonely thought silos, but rather limitless musings.

Maybe I need to be a bit more like Holden Caulfield, like the grey expanse before me. Perhaps I need to remind myself to be multifunctional long after this trip ends. Such existential ponderings, though, would have to wait. After reading a single chapter, I decided to go back to bed. The sea aside, no one was awake. And hey – aren’t vacations for relaxing anyway?

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

Serving its palatial purpose

I’m continually reminded how young – and perhaps how juvenile – the States can be. Serving Old Town Scottsdale since 1993! A fixture in the community for half a century! A heritage home built at the turn of the century awaits you! The pre-AIDS free love era of the seventies is this abstract construction I can’t quite understand, whereas the era of powdered wigs and clandestine pathways to freedom is nearly unfathomable. We are, for better or for worse, obsessed with the todays and the tomorrows, not necessarily the yesterdays, much less the yesteryears.

Tradition and history are absolutely engrained here, despite the sounds of modern life continually bombarding you, from the nasal horns of tiny cars to continual whir of air conditioning fans. Somewhere a shopkeeper throws open the gates to his matchbox-sized niche of commerce and a cell phone plays an oddly familiar tune. Wait? Could that be? Why, yes. Yes, it is. It’s Lady Gaga.

Perhaps the most contradictory, not to mention enchanting, is the fact that this all occurs at the steps of some of the most stunning temples and architectural dreamworks to adorn the planet. It takes me a second to process the fact that text messages are being sent beneath the gaze of Ganesha, this version lovingly and skillfully carved in cloudy marble nearly 500 years ago.

Interacting with these structures and each of their sculptural details has quickly become one of my favorite ways to musingly pass an afternoon. Nothing like a few hours spent with cornices, mosaics, turrets, and religious idols, right?

Naturally, I wanted to go see the Rambagh Palace in Jaipur. Resting on a throne of 47  manicured acres, it regally resists the urban bedlam outside its gates. What’s distinct about this particular palace, however, is the fact that it’s no longer maintained by the Indian government or even some benevolent NGO. It was converted into a 5-star resort, owned and maintained by the Taj Hotels group, where a single evening can deduct up to $13,000 from your bank account. The median income in Rajahstan, in which Jaipur is the capital, is $700. Per year.

manicured acres, it regally resists the urban bedlam outside its gates. What’s distinct about this particular palace, however, is the fact that it’s no longer maintained by the Indian government or even some benevolent NGO. It was converted into a 5-star resort, owned and maintained by the Taj Hotels group, where a single evening can deduct up to $13,000 from your bank account. The median income in Rajahstan, in which Jaipur is the capital, is $700. Per year.

manicured acres, it regally resists the urban bedlam outside its gates. What’s distinct about this particular palace, however, is the fact that it’s no longer maintained by the Indian government or even some benevolent NGO. It was converted into a 5-star resort, owned and maintained by the Taj Hotels group, where a single evening can deduct up to $13,000 from your bank account. The median income in Rajahstan, in which Jaipur is the capital, is $700. Per year.

manicured acres, it regally resists the urban bedlam outside its gates. What’s distinct about this particular palace, however, is the fact that it’s no longer maintained by the Indian government or even some benevolent NGO. It was converted into a 5-star resort, owned and maintained by the Taj Hotels group, where a single evening can deduct up to $13,000 from your bank account. The median income in Rajahstan, in which Jaipur is the capital, is $700. Per year.My curiosity was piqued. Also – let’s be honest – I wanted a stiff cocktail, an indulgence not found in my budget accommodations.

Surprisingly (or not?) Rambagh Palace was the most beautifully restored palace I have seen thus far. Each marble carving was exquisite, every plant tended to, each wall perfectly smooth and painted, every mosaic intact and gleaming, each alabaster chandelier wired and glowing. Peacocks roamed the grounds. The scent of jasmine welcomed you as you were met by a genuflection and a Namaste. The lighting was perfect. I mean, it’s one o f those places where everybody looks good. Compact fluorescents be damned, Rambagh made sure everyone was cast in a flattering light.

f those places where everybody looks good. Compact fluorescents be damned, Rambagh made sure everyone was cast in a flattering light.

f those places where everybody looks good. Compact fluorescents be damned, Rambagh made sure everyone was cast in a flattering light.

f those places where everybody looks good. Compact fluorescents be damned, Rambagh made sure everyone was cast in a flattering light.As I sat there attempting to blend in, a teacher amongst a calm sea of executives, I couldn’t help but think about the original intention of the palace. Yes, of course, it was a home for the maharaja; but it was also an ostentatious display of his wealth. The wealthy and the royal from near and far would come to be entertained, wined, and dined. Perhaps his power was best shown by the caliber of the entertainment, the gastronomic spread, the overall splendor of the evening.

Ironically, not much has changed. Live music still soothes. Dance performances still awe. The wealthy are still surrounding the courtyard. And the regal? Well, Anderson Cooper and his boyfriend came here not long ago, and as a Vanderbilt descendent, he’s about as close as we come to American royalty. There has been, however, a slight power change. No longer is it the host who must flaunt his riches, but rather the guest. The question becomes, then, how much is he or she willing to spend? How much is this temporary utopia worth? What can Rambagh Palace charge for the re-creation of an era and a giant pair of rosy glasses? For me, apparently, that cost was a twelve dollar drink. For those around me, that cost was much more.

As I left that night, slipping back into Rajahstani reality, I found myself haggling with a rickshaw driver over ten rupees, less than a quarter. I felt dirty. Was I that willing to give my money to the Taj Hotels but not to the man who safely returned me to my much more meager lodgings?  What did this say about me? About the influence of clever marketing? Why are we willing to pay so much put ourselves in an environment that someone has decided is pleasurable? Desirable? Worthy of hoards of cash?

What did this say about me? About the influence of clever marketing? Why are we willing to pay so much put ourselves in an environment that someone has decided is pleasurable? Desirable? Worthy of hoards of cash?

What did this say about me? About the influence of clever marketing? Why are we willing to pay so much put ourselves in an environment that someone has decided is pleasurable? Desirable? Worthy of hoards of cash?

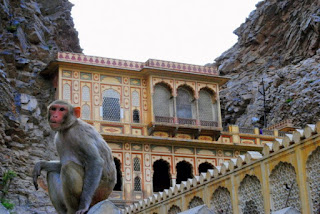

What did this say about me? About the influence of clever marketing? Why are we willing to pay so much put ourselves in an environment that someone has decided is pleasurable? Desirable? Worthy of hoards of cash? The next day, I took in the sunset at Galta (aka the Monkey Palace) where a series of amber structures honored the Hindu deity Hanuman. Tucked away between soaring mountains, it’s a fascinating place – simian families parallel the human ones, men and women bathe and swim in a pool fed by a single stream of water coming from the mouth of a carved sacred cow. It’s indescribably ambient and tranquil, two words I would have also used to describe the previous night at Rambagh Palace. Authenticity, however, is lost at Rambagh. The cost of Galta? 100 rupees. $2.16.

I find it poignant that I’m writing this as I sit in the Mumbai airport, a layover en route to Bengalaru to visit the lovely Mangala. I’m paying for this atmosphere. It’s sterilized, anglicized under the smooth curves of modern architecture. Slick red chairs rest next to triangular stainless steel planters. The digitized tonal trio introduces a boarding announcement, entirely in English. I wait a moment for the Hindi or Marathi version, almost as an afterthought, but one never comes. I sip my four dollar coffee.

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Dirty flip flops

I stepped in shit yesterday. While wearing flip flops. It could have been from a cow, a pig, perhaps a donkey or a horse, maybe even a camel – all animals that wander the streets of Jaipur. I did that

awkward drag-your-foot-across-the-ground shuffle until most of it was off, except for that bit on my toe. Eww. A trio of women laughed at me, which I can’t be upset about because I would have done the same thing. Had this happened to me back home (although it would have assuredly been dog excrement – not too many camels roam Brooklyn), I would have let loose a litany of f-bombs. Mothers from a two-mile radius would have had to cover their children’s ears. Here I just shrugged. With animals an integral part of urban life in Jaipur, it happens. Why let a little poo ruin a perfectly good day?

awkward drag-your-foot-across-the-ground shuffle until most of it was off, except for that bit on my toe. Eww. A trio of women laughed at me, which I can’t be upset about because I would have done the same thing. Had this happened to me back home (although it would have assuredly been dog excrement – not too many camels roam Brooklyn), I would have let loose a litany of f-bombs. Mothers from a two-mile radius would have had to cover their children’s ears. Here I just shrugged. With animals an integral part of urban life in Jaipur, it happens. Why let a little poo ruin a perfectly good day?Jaipur has been great. With over 4 million people living here, a small city it is not; yet, it’s calmer, friendlier, a touch slower. The chaos is still here, of course, but it’s toned down, like Delhi on a tired Sunday afternoon. Maybe it’s the ov erwhelming summer heat – a climatic repression I have never experienced before, not even in Arizona. This, too, you just sort of accept. So the crotch of my pants is wet with sweat. So I have tan lines which are bound for ridicule when I come home. Big deal. There are men on bike rickshaws who survive with a smile on their glistening faces, so I can handle some sweaty underwear.

erwhelming summer heat – a climatic repression I have never experienced before, not even in Arizona. This, too, you just sort of accept. So the crotch of my pants is wet with sweat. So I have tan lines which are bound for ridicule when I come home. Big deal. There are men on bike rickshaws who survive with a smile on their glistening faces, so I can handle some sweaty underwear.

erwhelming summer heat – a climatic repression I have never experienced before, not even in Arizona. This, too, you just sort of accept. So the crotch of my pants is wet with sweat. So I have tan lines which are bound for ridicule when I come home. Big deal. There are men on bike rickshaws who survive with a smile on their glistening faces, so I can handle some sweaty underwear.

erwhelming summer heat – a climatic repression I have never experienced before, not even in Arizona. This, too, you just sort of accept. So the crotch of my pants is wet with sweat. So I have tan lines which are bound for ridicule when I come home. Big deal. There are men on bike rickshaws who survive with a smile on their glistening faces, so I can handle some sweaty underwear.After a bus ride from Fatehpur Sikri (an adventure in and of itself), I got here Friday afternoon. I happened to see an ad for a new Bollywood movie, Milenge Milenge, opening that evening, and as coincidence would have it, Jaipur has the largest Bollywood cinema in all of India. Duh. Of course I wanted to go.

I had an hour to kill after buying my ticket. A sign for ice cream lured me across the street, and within moments I was alternating between sipping a chocolate shake (traditional Indian snack, right?) and holding the cup against my forehead. Damn, it was hot. My pants were spotted with sweat. I pretty much forgot about that, though, as the two young men next to me struck up a conversation.

“How do you find India?” Shocking he didn’t think I was from here.

“It’s amazing, actually. I’m really enjoying it.”

“Where do you come from?” Only the one next to me was talking. He was muscu lar with curly hair, fair-skinned. He didn’t appear to be from India, but I couldn’t place his accent. His friend, a bit scrawnier, longer-haired, didn’t say anything. I presumed it was a question of language.

lar with curly hair, fair-skinned. He didn’t appear to be from India, but I couldn’t place his accent. His friend, a bit scrawnier, longer-haired, didn’t say anything. I presumed it was a question of language.

lar with curly hair, fair-skinned. He didn’t appear to be from India, but I couldn’t place his accent. His friend, a bit scrawnier, longer-haired, didn’t say anything. I presumed it was a question of language.

lar with curly hair, fair-skinned. He didn’t appear to be from India, but I couldn’t place his accent. His friend, a bit scrawnier, longer-haired, didn’t say anything. I presumed it was a question of language.“The US. I live in New York. What about you?”

There was a pause. The curly-haired one tilted his head to the side a bit, a small smile appearing. It wasn’t an expression of joy or humor, rather one of hesitation, the result of pairing a grin with somewhat saddened eyes. “We’re from Afghanistan.”

There was a silent second after his response that screamed with the current tensions between the two countries. How do I respond? Do I say, “Hi. I’m from the US and we have a huge military presence in your country. What do you think about that? Sorry about all those dead civilians, by the way.” Of course not. The  second of silence seemed to have already said that.

second of silence seemed to have already said that.

I said the only thing that came to mind. “Hi, I’m Joe. It’s so nice to meet you.” I extended my hand. He took it, smiling.

second of silence seemed to have already said that.

second of silence seemed to have already said that.I said the only thing that came to mind. “Hi, I’m Joe. It’s so nice to meet you.” I extended my hand. He took it, smiling.

“I’m Haji Mohammad and this is Abdul Mosaver.” They were absolutely lovely and we talked for an hour. Haji and Abdul were working for their families who exported lapis lazuli from Afghanistan to Jaipur. Apart from explaining to me the details of that endeavor, we talked about Islam. It’s shocking how little I know about one of the world’s major religions, so they were happy to fill me in. Our chat floated to linguistic differences, and before I knew it I was practicing how to write both Joseph and Yusuf in Arabic. I had the precision of a mule. My attempts looked like ink regurgitations next to Haji’s beautiful script. After exchanging email addresses, we bid adieu.

I ran across the street to the Raj Mandir, the famed movie palace. As I breezed into the lobby, I stopped. It looked like a giant art deco birthday cake at a Barbie-themed party. The pink mirrored walls seemed to belong in Sydney’s bedroom, not a Bollywood movie house. The theater itself was a swath of buttercream frosting dotted with red exit signs instead of edible silver balls. Its grandeur wasn’t lost on the rest of the patrons as the dimness was punctuated with flashes from their cameras. Sadly, I’d left mine at the hotel.

Oh – and the movie? A pretty bad story, from what I understood, but those choreographed numbers that unabashedly used a massive fan for flowing hair and unbuttoned shirts more than made up for it.

The tw o days since then have been filled with all sorts of Rajhastani fun, from the marble elephants of the City Palace to the real ones outside the Amber Fort. There was a delightful chat with the caretaker of a Hindu temple who showed me countless photos of his guru. There was the unbelievably bizarre trip to Chokhi Dahni, a dining destination cum theme park that is the love child of Disney, Renaissance Fairs, and the entire Indian state of Rajhastan. There was the visit to Jantar Mantar, a series of sculptural tools built in the 1700s to track celestial movements and time. It’s ama

o days since then have been filled with all sorts of Rajhastani fun, from the marble elephants of the City Palace to the real ones outside the Amber Fort. There was a delightful chat with the caretaker of a Hindu temple who showed me countless photos of his guru. There was the unbelievably bizarre trip to Chokhi Dahni, a dining destination cum theme park that is the love child of Disney, Renaissance Fairs, and the entire Indian state of Rajhastan. There was the visit to Jantar Mantar, a series of sculptural tools built in the 1700s to track celestial movements and time. It’s ama zing how beautiful manifestations of numbers and astronomy can be. Math teachers: Jantar Mantar is your dream field trip.

zing how beautiful manifestations of numbers and astronomy can be. Math teachers: Jantar Mantar is your dream field trip.

o days since then have been filled with all sorts of Rajhastani fun, from the marble elephants of the City Palace to the real ones outside the Amber Fort. There was a delightful chat with the caretaker of a Hindu temple who showed me countless photos of his guru. There was the unbelievably bizarre trip to Chokhi Dahni, a dining destination cum theme park that is the love child of Disney, Renaissance Fairs, and the entire Indian state of Rajhastan. There was the visit to Jantar Mantar, a series of sculptural tools built in the 1700s to track celestial movements and time. It’s ama

o days since then have been filled with all sorts of Rajhastani fun, from the marble elephants of the City Palace to the real ones outside the Amber Fort. There was a delightful chat with the caretaker of a Hindu temple who showed me countless photos of his guru. There was the unbelievably bizarre trip to Chokhi Dahni, a dining destination cum theme park that is the love child of Disney, Renaissance Fairs, and the entire Indian state of Rajhastan. There was the visit to Jantar Mantar, a series of sculptural tools built in the 1700s to track celestial movements and time. It’s ama zing how beautiful manifestations of numbers and astronomy can be. Math teachers: Jantar Mantar is your dream field trip.

zing how beautiful manifestations of numbers and astronomy can be. Math teachers: Jantar Mantar is your dream field trip.As I think about my trip to Galta tomorrow, better known as the Monkey Palace because of its number one inhabita nt, I keep returning to the prevalence of animal life here. I just read a short piece of nonfiction called “Moby Duck” where the author posits that animals, once central to our existence and an inherent part of our everyday lives, have been marginalized. We animate them, turn them funny colors (Pluto? A yellow dog?), and transform them into non-biodegradable plastic toys. Is that the case here, though? Cows roam freely, some donning celebratory ribbons and fabrics. Elephants are honored in a yearly festival. Camels walk next to buses. Maybe this is just the modernized version of Noah’s ark. No matter the genus, two by two we walk along. Some of us just end up with a dirty flip flop.

nt, I keep returning to the prevalence of animal life here. I just read a short piece of nonfiction called “Moby Duck” where the author posits that animals, once central to our existence and an inherent part of our everyday lives, have been marginalized. We animate them, turn them funny colors (Pluto? A yellow dog?), and transform them into non-biodegradable plastic toys. Is that the case here, though? Cows roam freely, some donning celebratory ribbons and fabrics. Elephants are honored in a yearly festival. Camels walk next to buses. Maybe this is just the modernized version of Noah’s ark. No matter the genus, two by two we walk along. Some of us just end up with a dirty flip flop.

nt, I keep returning to the prevalence of animal life here. I just read a short piece of nonfiction called “Moby Duck” where the author posits that animals, once central to our existence and an inherent part of our everyday lives, have been marginalized. We animate them, turn them funny colors (Pluto? A yellow dog?), and transform them into non-biodegradable plastic toys. Is that the case here, though? Cows roam freely, some donning celebratory ribbons and fabrics. Elephants are honored in a yearly festival. Camels walk next to buses. Maybe this is just the modernized version of Noah’s ark. No matter the genus, two by two we walk along. Some of us just end up with a dirty flip flop.

nt, I keep returning to the prevalence of animal life here. I just read a short piece of nonfiction called “Moby Duck” where the author posits that animals, once central to our existence and an inherent part of our everyday lives, have been marginalized. We animate them, turn them funny colors (Pluto? A yellow dog?), and transform them into non-biodegradable plastic toys. Is that the case here, though? Cows roam freely, some donning celebratory ribbons and fabrics. Elephants are honored in a yearly festival. Camels walk next to buses. Maybe this is just the modernized version of Noah’s ark. No matter the genus, two by two we walk along. Some of us just end up with a dirty flip flop.

Saturday, July 10, 2010

21 questions. (Really. I counted.)

Somewhere between Agra and Jaipur rests Fatehpur Sikri, a town mostly known for its towering Jama Masjid and a fortress from the sixteenth century. Constructed under the reign of Emperor Akbar, not only does it house his own palace, but the treasury, an astronomer’s kiosk, a square where transgressors were trampled to death by elephants (no, really), and – what I found most intriguing – palaces for each of his three favorite wives. Hats off to Mother Nature’s design skills, too, because you’d think that an entire town built of red sandstone would be somewhat monotonous, but as the sun set, the walls burst into glorious flames. That solitary substance was transformed into infinite hues of the same color palette. Sherwin Williams: get ye to Fatehpur Sikri.

each of his three favorite wives. Hats off to Mother Nature’s design skills, too, because you’d think that an entire town built of red sandstone would be somewhat monotonous, but as the sun set, the walls burst into glorious flames. That solitary substance was transformed into infinite hues of the same color palette. Sherwin Williams: get ye to Fatehpur Sikri.

It’s been two days since I strolled in and out of the three wives’ palaces and I cannot stop thinking about them. While multiple wives was and continues to be nothing new, Akbar was unique in his religious tolerance: one wife was Muslim, one Hindu, and one Christian. Can you imagine the conversations that took place based solely on religion? Did the Muslim wife don a burka? The Hindu wife a sari? What about the Christian wife? Which was the holy day? The entire weekend? What about dietary restrictions? Did they each follow their own religion’s culinary doctrines or did they band together in solidarity?

thinking about them. While multiple wives was and continues to be nothing new, Akbar was unique in his religious tolerance: one wife was Muslim, one Hindu, and one Christian. Can you imagine the conversations that took place based solely on religion? Did the Muslim wife don a burka? The Hindu wife a sari? What about the Christian wife? Which was the holy day? The entire weekend? What about dietary restrictions? Did they each follow their own religion’s culinary doctrines or did they band together in solidarity?

Seriously - the questions just keep coming. Especially when I let my mind wander beyond religion and into how evenings were spent…

What was the stroll like from the wives’ palaces to that of the emperor? Was it a solitary affair, quietly slipping through the night sky? Was it marked with processional pomp? Was it a casual stroll, perhaps with the aid of a servant or two? Did she take an overnight bag? Did they get together and gossip over tea? Discuss the current state of the land? The weather? Sex? If they discussed the latter, was it a blushing discussion full of double entendres or was it a bawdy girls’ night?

I can’t stop. For whatever reason, I’m completely obsessed with thinking about the particulars of their marriage. Further fueling my internal inquisitions is the fact that each of the three wives’ palaces was a different size and incorporated varying architectural details. The Muslim wife got the grandest of the three, while the structure belonging to the Hindu wife was the smallest. One could argue, though, that hers had the greatest carvings and the best views of the compound’s courtyard. A sucker for a great vista, I’d say that the Christian wife got the best real estate with windows that looked out over the plains.

Wondering if they had these same thoughts, I began to wonder if jealousy is a natural human trait or some cultural construction. Are we prewired to want what someone else has? All major religions – to the best of my knowledge – have their ascribed moral compasses and each talk about the need to avoid envy, whether it is in regards to your neighbor’s wife, livestock, or iPad. If we are prone to such covetous behavior, then, is it possible that these three women were friends?

Maybe the reason I’ve spent so much time thinking about these undoubtedly fascinating women is because I’ll never know the answer to any of my inquiries. I can believe what I want to believe. They are – and will continue to be – characters of my own creation. Now that you, too, know the story of Akbar maybe the question to end all questions is this: How do your three wives vary from my three wives?

each of his three favorite wives. Hats off to Mother Nature’s design skills, too, because you’d think that an entire town built of red sandstone would be somewhat monotonous, but as the sun set, the walls burst into glorious flames. That solitary substance was transformed into infinite hues of the same color palette. Sherwin Williams: get ye to Fatehpur Sikri.

each of his three favorite wives. Hats off to Mother Nature’s design skills, too, because you’d think that an entire town built of red sandstone would be somewhat monotonous, but as the sun set, the walls burst into glorious flames. That solitary substance was transformed into infinite hues of the same color palette. Sherwin Williams: get ye to Fatehpur Sikri.It’s been two days since I strolled in and out of the three wives’ palaces and I cannot stop

thinking about them. While multiple wives was and continues to be nothing new, Akbar was unique in his religious tolerance: one wife was Muslim, one Hindu, and one Christian. Can you imagine the conversations that took place based solely on religion? Did the Muslim wife don a burka? The Hindu wife a sari? What about the Christian wife? Which was the holy day? The entire weekend? What about dietary restrictions? Did they each follow their own religion’s culinary doctrines or did they band together in solidarity?

thinking about them. While multiple wives was and continues to be nothing new, Akbar was unique in his religious tolerance: one wife was Muslim, one Hindu, and one Christian. Can you imagine the conversations that took place based solely on religion? Did the Muslim wife don a burka? The Hindu wife a sari? What about the Christian wife? Which was the holy day? The entire weekend? What about dietary restrictions? Did they each follow their own religion’s culinary doctrines or did they band together in solidarity?Seriously - the questions just keep coming. Especially when I let my mind wander beyond religion and into how evenings were spent…

What was the stroll like from the wives’ palaces to that of the emperor? Was it a solitary affair, quietly slipping through the night sky? Was it marked with processional pomp? Was it a casual stroll, perhaps with the aid of a servant or two? Did she take an overnight bag? Did they get together and gossip over tea? Discuss the current state of the land? The weather? Sex? If they discussed the latter, was it a blushing discussion full of double entendres or was it a bawdy girls’ night?

I can’t stop. For whatever reason, I’m completely obsessed with thinking about the particulars of their marriage. Further fueling my internal inquisitions is the fact that each of the three wives’ palaces was a different size and incorporated varying architectural details. The Muslim wife got the grandest of the three, while the structure belonging to the Hindu wife was the smallest. One could argue, though, that hers had the greatest carvings and the best views of the compound’s courtyard. A sucker for a great vista, I’d say that the Christian wife got the best real estate with windows that looked out over the plains.

Wondering if they had these same thoughts, I began to wonder if jealousy is a natural human trait or some cultural construction. Are we prewired to want what someone else has? All major religions – to the best of my knowledge – have their ascribed moral compasses and each talk about the need to avoid envy, whether it is in regards to your neighbor’s wife, livestock, or iPad. If we are prone to such covetous behavior, then, is it possible that these three women were friends?

Maybe the reason I’ve spent so much time thinking about these undoubtedly fascinating women is because I’ll never know the answer to any of my inquiries. I can believe what I want to believe. They are – and will continue to be – characters of my own creation. Now that you, too, know the story of Akbar maybe the question to end all questions is this: How do your three wives vary from my three wives?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)